All Climate Change Is Local

By Fen Montaigne / 8 minute read

The 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Explanatory Reporting was awarded to the staff of The Washington Post for a compelling series of articles titled “2 Degrees C: Beyond the Limit” — a reference to the looming 2 degrees Celsius (3.6° Fahrenheit) increase in temperatures beyond which scientists warn the world could face destabilizing global warming. The fact is, however, that as greenhouse-gas emissions continue to soar, many places around the world are already experiencing the effects of reaching or exceeding the 2° C increase in temperatures. The Washington Post’s staff visited a dozen of these places — from California to Siberia, from Qatar to Australia — to chronicle how temperature increases are affecting the environment and people’s lives.

The series highlighted a fundamental truth about climate-change coverage: rising temperatures are already affecting nearly every region of the U.S. and the world. This global approach was impressive, but it’s not required to cover this issue. Local publications, TV and radio stations, and other storytellers need look no farther than their own counties, states, or regions to find these stories.

Along overbuilt coastlines, rising seas will be felt by everyone in the coming decades, with sea levels expected to increase as much as six feet by 2100. In the Rocky Mountain West, steadily rising temperatures and intensifying drought are leading to more intense and frequent wildfires. In many parts of the country, extreme precipitation events and flooding are on the rise because a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture.

If you are an editor or reporter and can’t find the evidence of climate change in your city or state, you’re not looking hard enough. Seasons are shifting, species are on the move, and extreme weather events are on the rise. The list of possible stories includes what local officials are doing to mitigate intensifying floods; changes needed in building codes to deal with the effects of climate change; the impact on insurance rates; the effects on agriculture; and the potentially devastating effects on the municipal budgets of coastal communities as rising sea levels force the funding of costly projects to hold back the sea.

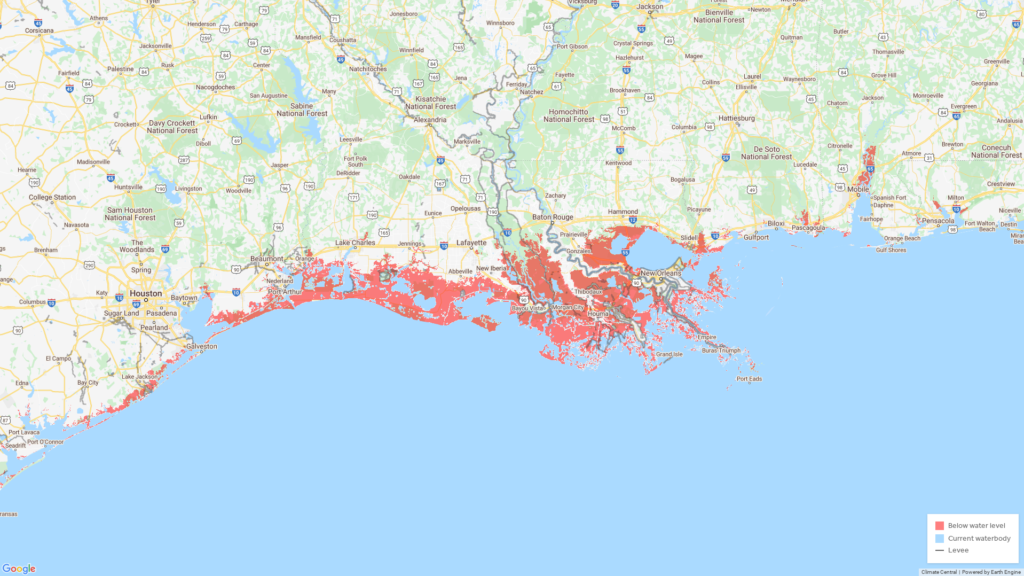

Climate Central, a nonprofit research-and-news organization, understands better than most the powerful impact of showing readers how global warming is already changing their towns and cities, and what is likely to come. The site has posted interactive maps and graphs illustrating how different regions are being affected by rising temperatures, increased precipitation, and other weather extremes. A widely viewed interactive tool, Surging Seas, showed how different coastal locales will be affected by sea levels as they rise this century by one foot, three feet, and beyond.

Among many other examples of news reports on the growing impact of climate change in local regions:

- The California-based nonprofit news organization Reveal, partnering with the San Francisco public-radio station KQED, did a series of podcasts and written reports on the devastating Northern California wildfires in 2017 that killed 44 people and destroyed thousands of buildings.

- The nonprofit Pulitzer Center supports a project called Connected Coastlines, which works with a consortium of newsrooms and independent journalists to cover the impact of climate change on U.S. coastal regions.

- A similar effort, The Invading Sea, is a collaboration of 25 Florida news organizations — including the Miami Herald, Orlando Sentinel, and the South Florida public-radio station WLRN — reporting on global warming and sea-level rise in the state.

- National Public Radio did a report showing that the urban “heat island” effect is most pronounced in low-income, minority neighborhoods that have historically been subjected to redlining — the practice by which banks and other institutions withhold mortgages and other investments from certain communities.

Among the editors and writers who have grasped the importance of bringing global-warming coverage to the local level is Lyndsey Gilpin, founder of Southerly, a nonprofit news organization covering ecology and environmental justice in the South. Working in a region where skepticism about climate change runs deeper than in many parts of the country, Gilpin has learned that a key way to connect with readers is to listen to their stories about how a changing climate is affecting their communities.

“The view of climate change has changed a lot in the South in just the last few years,” says Gilpin, who started Southerly in 2016. “But because of the fossil-fuel disinformation campaign and the [conservative] media for years giving climate deniers platforms, the subject is politicized. That conversation has alienated so many people. But there are ways to `balance’ this out by talking about climate change in ways that are more acceptable, so often we focus our stories around extreme weather, like flooding, heat waves, the impact of rain or drought on farmers or local businesses. Covering local impacts makes so much more sense to me, because people always want to protect what’s around them.

“To be honest, I don’t care what people call climate change, so long as they are willing to do what needs to be done to respond to it,” Gilpin says. “They may not be ready to jump into a climate strike, but they see what’s happening where they live and how it’s changing, and they are looking for people to listen to them. Looking at those kinds of community-level stories builds trust between journalists and readers.”

The view of climate change has changed a lot in the South in just the last few years.

Lyndsey Gilpin, founder, Southerly

Some of what Southerly has published on the local impacts of global warming include articles on the public-health problems created by worsening floods in Appalachia, on the dilemma faced by residents of coastal Louisiana as their properties repeatedly flood in worsening hurricanes and tropical storms, and on the threat that increased flooding and rising seas pose to historic African American sites in the South.

The article on the dangers facing neglected Black sites looked at historic and cultural locations, such as cemeteries, at risk in Texas, Florida, Mississippi, and North Carolina. By connecting circumstances across a state or region, Gilpin says, reporters and editors can inform and empower residents about how similar communities are dealing with problems created by climate change.

Another important lesson for editors, says Gilpin, is that when assigning and reporting on situations like the plight of neglected Black historical sites, it’s vital to look at what inequities — both historical and current — have led to those problems. In the case of some African American cemeteries, Southerly’s story noted that these burial sites had often been relegated to marginal areas vulnerable to floods and other forms of environmental degradation.

“When reporting on any low-income community dealing with environmental hazards or sea-level rise, you should look at the context of how they got there and what systems are keeping them there,” she says. “And the people most at risk often have the fewest resources to do something about that. We’re going to see these stories more and more, and we have to ask what are the political and economic systems that force people to be in these situations, and how do we hold the right people or agencies or companies accountable?”

That emphasis on the importance of speaking with people about how their own communities are changing, and what is behind it, was at the heart of a 2018 series, “Finding Middle Ground: Conversations Across America,” in InsideClimate News. For the series, Meera Subramanian interviewed diverse groups — ranchers, fishermen, farmers, evangelical Christians — about how global warming was affecting their lives.

“It’s very challenging to get someone interested in something that’s too far away or too unclear,” says Meaghan Parker, executive director of the Society of Environmental Journalists. “Focusing on stories locally is a powerful way to explain issues but also to connect to your audience. And it’s not only about impacts but also about opportunities and solutions.”

Local Accountability, Local Experts

As the adverse effects of a warming world intensify, growing numbers of local, state, and national officials are pledging to do something about the threat. But the gap between words and deeds can be wide. Weaning modern economies off fossil fuels is a monumental challenge, and helping communities adapt to climate disruption is complex and expensive.

Still, in the coming years, editors and reporters will need to increase their efforts to hold officials accountable for failing to take steps to reduce emissions or help their communities live with climate change. For example, if places in South Florida are already regularly experiencing flooded streets from rising sea level, why do officials continue to approve billions of dollars in new construction? In the American West, why are local and state administrators still allowing houses to be built in areas vulnerable to a growing number of wildfires? As coastal storms get worse, why are local, state, and federal authorities allowing repeated rebuilding in vulnerable, storm-damaged communities like Dauphin Island, Alabama, or pursuing policies that are bankrupting the federal flood-insurance program?

“The main thing is climate is not just an environmental story, and it’s not just a science story,” says Banerjee, of NPR. “It is everything. It’s a real-estate story. It is a national-security story. It is a corruption story. It is a health story. One of the best ways to write about the climate, whether on the national level or local level, is through the lens of accountability.”

The many scientists, agricultural-extension agents, conservationists, and other experts at the local or state level are an important resource. Every state has university researchers who study the regional impacts of climate change. State-government climatologists can be excellent sources. State and local agricultural experts know best how a changing climate is affecting farming.

Putting the Science Into Context

Some of the impacts of global warming are rapid, dramatic, and unequivocal, none more so than the changes that have swept across the Arctic over the past 40 years. While average global temperatures have increased by close to 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880 — with two-thirds of that warming since 1975 — the Arctic has been warming far more rapidly. The extent of Arctic Ocean ice in summer is about half what it was when satellite monitoring began, in 1979, and the volume of Arctic sea ice has declined as thick, multiyear ice disappears. The Arctic Ocean may largely be ice-free in summer by 2040 or 2050.

Other climatic changes, however, are less stark and less well understood. So when editing stories on the many shifts now underway globally, it’s important to be wary of exaggeration (things are bad enough without exaggerating) and to put the latest findings in context, showing readers and viewers that a range of future scenarios exists.

Although the overall trend of planetary warming is clear, scientists are still trying to sort out issues that involve the complex interaction of global atmospheric and ocean currents. When will rampant deforestation, increasing temperatures, and intensifying drought turn the vast Amazon rainforest from a massive absorber of CO2, or sink, into a CO2 source? Will the steady melting of Arctic permafrost lead to the release of a so-called “methane bomb” from thawing soil and wetlands, causing a catastrophic release of methane? (Methane lingers for only decades in the atmosphere, as opposed to carbon dioxide’s centuries, but methane has a heat-trapping capability roughly 30 times that of CO2.) How profoundly will marine ecosystems be affected by acidification caused by the world’s oceans absorbing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide?

These and many other questions are under study. And when research comes out, stories should put the latest findings in a larger framework and not inflate any one study into a world-changing revelation.

“All of these impact questions are really hard, and there’s a tremendous amount of uncertainty,” says Justin Gillis, the former climate reporter at The New York Times. “Climate modeling is a legitimate enterprise. It gives us the best answers we’re going to be able to have in current time to uncertain questions. But nobody pretends that climate modeling doesn’t have big holes or big blind spots. I think the way to think about this is that’s it’s a problem in risk management. What the science has done is outline this distribution of risks.

“If you’re confronting a new study and trying to figure out what to write about it,” Gillis says, “the first thing I would tell my reporter to do is figure out where this fits in the longer thread, in the larger scientific context. How might this study change the consensus? Will the study stand the test of time, or is there a history of outlier studies here that eventually get knocked down? Any given study is just one data point in this complicated enterprise of producing human knowledge, where it’s corrected and self-corrected. We routinely get things wrong but then, over the long run, we tack in the right direction.”

This can be a challenge for journalists, who often latch on to outliers as opportunities for interesting stories. But, some outliers are just errors or even expected variances within a normal distribution. Putting the proper context on any single piece of data is critical in order to understand the broader truth.