Finding Structure Without Losing Touch With Science

By Rachel Feltman / 4 minute read

Many of us, having grown up being told about geniuses like Stephen Hawking and Albert Einstein, develop a sense that science is a series of breakthroughs made by maverick scientists. But those are the exceptions. Most of the time, science is a slow, gradual process that involves the collaborative efforts of dozens — sometimes thousands — of people with different backgrounds and skill sets.

When scientists first detected gravitational waves, the general public was enthralled. But people heard mostly from a handful of already esteemed scientists, which meant that many enthusiastic readers didn’t realize that more than a thousand researchers, in various disciplines, had been crucial to the discovery.

When just three men received the Nobel Prize in Physics for the endeavor, Popular Science sought to highlight the discrepancy in a print article that featured every single name listed on the study, and noting the work of a few of the scientists who hadn’t yet been mentioned in press coverage.

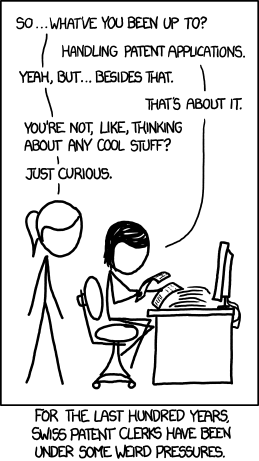

But the solution isn’t always as obvious as “give credit to the other 1,000 or so people involved.” Sometimes, breaking down the false narrative of the lone genius means looking for characters who aren’t scientists at all.

“It clearly serves the story well when you can make it about one character, their journey, their odyssey to solve the problem,” says Gideon Lichfield, of MIT Technology Review. “But the reality is that science doesn’t work that way a lot of the time.”

Lichfield suggests solving that problem by finding a main character other than the scientist doing the research. Consider a story about patients trying to get their problem cured when nobody in the medical world is paying attention. Such a story can still be heavy on the science, but focusing on the people affected by the science instead of the people doing the science itself — that’s a great way to avoid making it seem as if science is being done by lone geniuses.

A common mistake for editors would be to take any given finding as gospel.

Azeen Ghorayshi, science editor, BuzzFeed

Another misunderstanding about science comes down to the basic concept of “discovery.” Individual scientific studies do not close the book on the subject they investigate. It takes years of repeated experiments and tweaked questions to come up with definitive answers — if there are any. Stories are meant to have beginnings, middles, and endings; in science reporting, an editor has to realize that conclusions are almost never neat and tidy.

Azeen Ghorayshi, science editor of BuzzFeed, agrees. “There’s this fake idea that scientists are infallible, that discoveries are made in a vacuum, and that the accumulation of knowledge is linear — when really all of it is so much more messy than that.” The pandemic put this on display more clearly than ever, she notes. With Covid-19, “the production of knowledge is in overdrive, and information is being shared so rapidly that we’re seeing all the mistakes and foibles and dramas play out in real time. At the end of it, we’ve definitely learned a lot about this virus. But a common mistake for editors would be to take any given finding as gospel.”

That lack of clarity or certainty is a common challenge. Maddie Stone, of Earther, provides an example of this from her climate-change beat. “In climate journalism, editors and journalists alike have a strong tendency to impose the ‘X is a problem, and climate change will make it way worse’ narrative on just about any story,” she says. But in a lot of cases, while scientists think that something might be exacerbated by climate change — a certain type of extreme weather, for example — because of data limitations or the newness of the field, we can’t be sure.

Stone says editors should resist imposing simple narratives and instead embrace complexity. “Building uncertainty into our narratives, and telling important stories that subvert expected narratives, is not only intellectually honest — it gives readers a more complete understanding of how the scientific process works.”

The process of trying to find out why we don’t know something often makes a great narrative for building a feature.

Gideon Lichfield, editor in chief, MIT Technology Review

“There is a genre of tech and science stories which is all about, ‘These people came up with this thing, isn’t it cool? Maybe it could be used to solve problem X, but it’s too early to tell,'” says Lichfield. At the same time that it glorifies discovery, it also decontextualizes it, leaving readers none the wiser.

“The Covid-19 crisis has really clarified that for me,” Lichfield continues. “What we found people were really looking to read were explainers. But at some point, it became less about explaining how things worked and more about explaining why we don’t know how a thing works. It’s very honest, and a way to describe how science is difficult. The process of trying to find out why we don’t know something often makes a great narrative for building a feature.”

As is the case with any other piece of journalism, finding a narrative starts with asking what story you’re trying to tell. To summarize the sentiments above, a number of narrative tropes are unlikely to yield a scientifically accurate article that’s useful to your readers:

- The story of the great scientist who solved a big problem.

- The story of a breakthrough discovery.

But scientific stories are rich with other potential angles. Taking a unique tactic can yield fascinating characters and narratives that don’t inherently misrepresent the scientific process. For example:

- Focusing on people who are affected by a scientist’s work, rather than on the scientists themselves.

- Finding ways in which a scientist or a method differs from the norm, and exploring what problems the scientist was working to avoid with this innovation.

- Exposing science’s shortcomings — corruption, difficulty finding funding, misguided approaches to solving problems.

- Exploring how lesser-known members of the team — junior scientists, women, people of color, researchers with unusual backgrounds — contribute to the process.

- Asking why scientists turned out to be so wrong about something, or why a scientific problem is still too complex to solve.

Once you internalize these potential pitfalls and red flags, editing a science story into a compelling narrative should be no more difficult than doing so for another subject.