Introduction

By Yasmin Tayag / 3 minute read

As science journalists in the post-truth era, we are purveyors of facts at a time when they are regularly trumped by ideology, emotion, and “alternative facts.” As societies become more polarized, some people are becoming increasingly vulnerable to misinformation and conspiracy theories — and suspicious of the facts that we strive to communicate. When feelings regularly outweigh evidence, it’s tempting to give into cynicism: Why bother with the truth? But now more than ever, it’s critical to uphold it. While a minority of people are actively anti-science, far more are confused about whom to trust and what to believe. They, like everyone, want to hold beliefs that are correct. Science journalists are uniquely positioned to provide the information and guidance to help them do so.

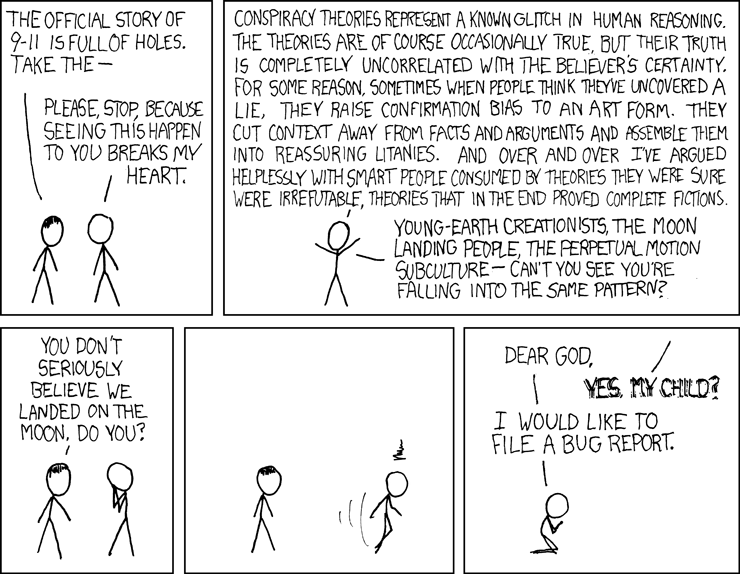

Communicating the facts is the first step. But when we confront misinformation, we don’t just tackle false claims and inaccuracies. We also confront everything else that supports its existence: world leaders who deliberately tout conspiracy theories, a loss of faith in the institutions and processes previously trusted to define truth from non-truth, a public that increasingly struggles to tell the difference between the two, and a media ecosystem that enables and accelerates all of the above. In addition, many people lack scientific literacy and misunderstand the scientific process. They are impatient for answers but don’t always realize how long science needs to produce them. The lack of information about the coronavirus at the early stages of the pandemic, for example, understandably led to global frustration. Unfortunately, misinformation tends to proliferate in the absence of clear answers.

Under these circumstances, addressing misinformation and conspiracy theories requires thoughtfulness and a good deal of delicacy. While it’s important to correct misinformation, calling attention to it can give it more credence than it deserves. I sometimes think of misinformation as an unruly pet: try too hard to control it and it lashes out and creates a noisy scene, but leave it unchecked and it tears up its surroundings. A firm but gentle hand is needed.

Science journalists alone, of course, can’t fix misinformation-promoting algorithms, oust politicians who promote lies, or alleviate the disillusionment that leads some people to believe in conspiracy theories. But we can communicate the facts in a way that is accurate, accessible, and memorable, in hope that those seeking to grasp truth can do so. This chapter is about how to do that without drawing undue attention to misinformation or contributing to it ourselves. It is also about building scientific literacy and trust in science to help people become less vulnerable to misinformation in the first place. The ideas presented here are informed by science editors, as well as by scholars who study science communication, whose findings are helping shape journalism’s best practices for dealing with misinformation.

When addressing misinformation, it’s important to remember that some people will refuse to change their minds about it, and that’s okay. It’s not the job of a science journalist to shift everyone’s worldviews. The goal is to be as effective as possible in providing support to people who struggle to understand what’s fact versus fiction — and are open to receiving help figuring it out.

Many science journalists covering vaccination, for example, have learned to discern between two groups of people: the anti-vaccine camp, who flat-out reject vaccination, and those who are “vaccine-hesitant” for a wide range of valid reasons. Efforts to clear up misinformation are largely focused on the latter group, because the members of the former are thought to be so deeply entrenched in their thinking that they are unlikely to change their minds. The latter, in contrast, could see through the fog of misinformation and learn what is actually true.

That is to say, communicating effectively about misinformation isn’t just about handing people the facts. The facts need to be shared in a way that people can receive. And that’s where good science journalism — and good editing — comes in.