Literary Devices

By Neel V. Patel / 4 minute read

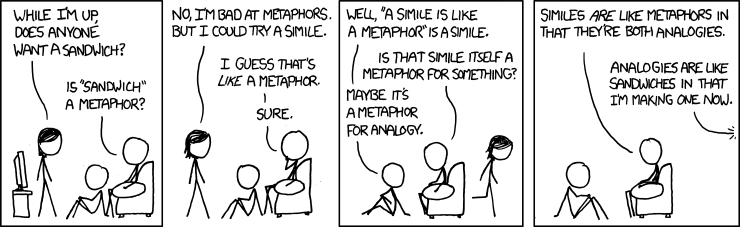

Most writing would be awfully dreary without the benefit of literary devices to help bring stories to life. In popular science especially, metaphors, analogies, similes, and imagery can go a long way toward making complex, opaque concepts and ideas understandable and relatable. Calling a virus an invading force helps us to understand that this bit of genetic material wrapped in a protein coat poses a threat. Saying that a supernova shines brighter than 10 billion suns provides at least some way to explain an object that is otherwise incomprehensibly bright.

We should encourage anything that helps make a popular-science story more engaging to readers — including the use of literary devices. “But you don’t want to overuse metaphors and analogies and so forth,” says NPR’s Andrea Kissack. An analogy should help directly explain something to the reader. It should not create another layer that needs to be parsed. It’s always important to ask whether a specific metaphor or analogy is actually useful or just prolongs the explanation.

Audio can often act as a sort of sonic equivalent to a literary device, with sounds or even music to help illustrate a science or tech concept. Kissack cites one Shortwave segment from October 2019 about “adversarial A.I.” experiments to help teach us how to fend off cyberattacks. The program includes a musical clip with subtle instrumental sounds — ones the average human would have big trouble identifying, but that A.I. would have no trouble picking out. The A.I. systems will have almost nothing to do with audio, but the 45-second musical example articulates the point very well: A.I. can discern things within a software system that are not apparent to a person.

MIT Technology Review‘s Niall Firth recently edited a story that he thought led with a brilliant analogy: “Running a health-care system is like juggling bees. Millions of moving pieces — from mobile clinics to testing kits — need to be in the right places at the right time. That’s even harder to do in countries with limited resources and endemic disease.” The passage works well because it not only provides one hell of a visual to grab the reader (bees being juggled!) but also articulates the chaos of the task at hand.

During her time at OneZero, Yasmin Tayag helped lead coverage of genetics research. One of her favorite metaphors was describing Crispr as “a pair of molecular scissors,” she says. Readers could get their heads around the idea that Crispr is a tool that can cut through DNA molecules in order to allow scientists to insert genetic pieces.

But most editors will caution against relying on literary devices to support a story. “Science is supposed to describe what something is, not what it is like,” says Tayag. You run the risk of making your story too artsy — which may be attractive to so many readers but may unintentionally distort the subject matter. (See the case study in the sidebar for an example.)

Firth is particularly wary of analogies and metaphors that do not have universal appeal. Not all readers around the world are going to understand what you mean by saying a team of engineers “hit a home run” with an experiment, or that a colorful display of the Northern lights was brighter than the sky on the Fourth of July. Even if your audience is primarily American, science stories are supposed to transcend borders and cultures. You can only improve your story’s reach by thinking about an international audience.

Michael Roston of The New York Times also advises science journalists against trying to anthropomorphize things. One story he edited, about a nine-year-old female Japanese macaque “monkey queen,” was initially filled with tropes about love. Roston pushed back: “These are monkeys,” he says. “We have no idea what their emotional states are and how much they relate to our own personal comprehension of relationships.”

Case Study

The Earth Used to Look Like Donald Trump

In February 2017, I was working as an associate editor for Inverse. Donald Trump had just been elected president — and even among popular-science writers there was a rush to try to fit a Trump peg into stories. At one point I found myself assigning a story about a study that suggested the ancient Earth might have actually had an orange, hazy glow 2.5 billion years ago. Since there was nothing more in vogue at the time than dunking on the former president’s orange complexion, I slapped a working headline on the story: The Earth Used to Look Like Donald Trump.”

The writer ran with it and even dropped in a few glib references to the president. NASA had provided a conceptual image of the planet in a press release, and we decided it would be a laugh to photoshop Trump’s hair onto the planet and add a crudely drawn face. And then we hit publish.

I instantly regretted this. The Trump analogy didn’t help anyone’s understanding of the research. (There was already a picture to show readers!) It didn’t make the science behind the story easier to grasp. (Iin fact, it probably had the opposite effect.) And while some readers may have enjoyed seeing the president lampooned, it very likely turned off other readers, who were simply interested in learning about some peculiar planetary science. Science can be political, and it is important to engage in those politics when warranted — but there is no good reason to add an unnecessary political dimension to a story.

Literary devices play a more crucial role in audio stories. In radio and audio podcasts, “you can’t see anything,” says Kissack. “It really helps to be able to say the NASA sunshield is as big as a school bus.” Audio is an exercise in being as descriptive as possible.

At the same time, Feltman still urges restraint: “I kind of treat metaphors and similar constructions the same way I treat humor in a draft. If it’s there, and it lands, that’s great. But forcing it is so much worse than not having it at all.”

“If your story cannot be understood without a metaphor,” she argues, “people just won’t understand it at all. And that’s a different problem.”

Not every editor would agree with that — I’m not sure I do. But I understand her point that overreliance on a literary device might be an indication that you’ve failed to properly explain the science itself. Such devices should be tools for explaining science — not substitutes for a layperson’s explanation itself. It’s something Karen Kaplan of The Los Angeles Times echoes in the next section, on jargon.