Science and Denial

By Fen Montaigne / 7 minute read

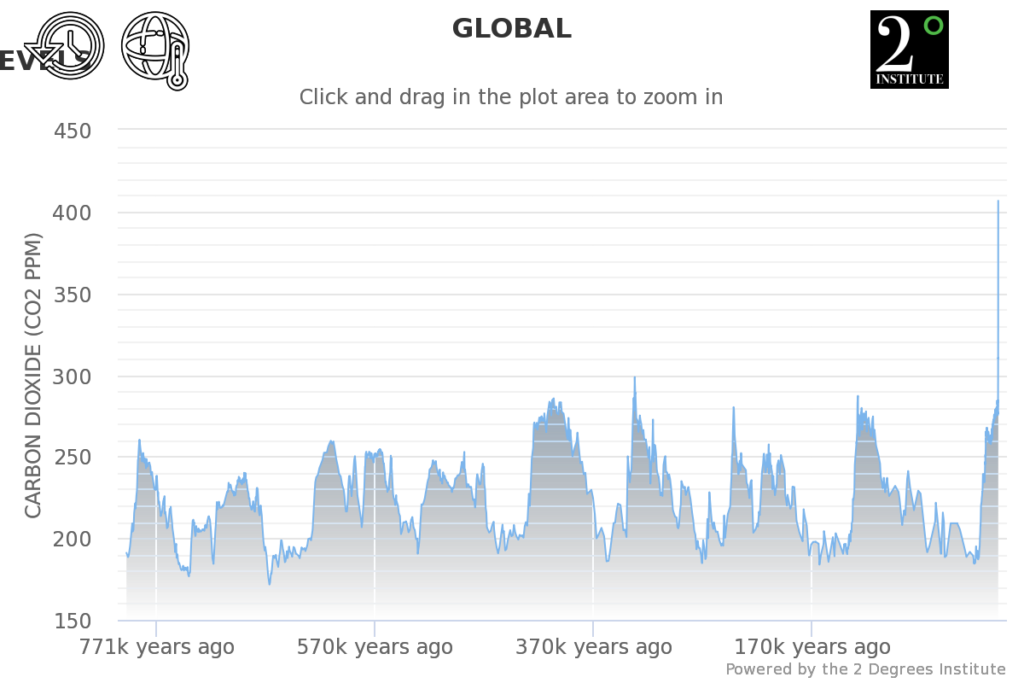

The reason the earth is rapidly warming is grounded in a law of physics as immutable as the law of gravity. The greenhouse effect, which has been an established scientific principle since the 19th century, says that certain gases — most notably carbon dioxide and methane — can, at even small concentrations, trap heat in the atmosphere. Based on studies of air bubbles in polar ice cores, scientists know that atmospheric CO2 concentrations are at their highest levels in at least 800,000 years, as human activity pumps 30 billion to 35 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere annually. Global temperatures are rising accordingly.

As of the summer of 2020, the five hottest years since reliable record-keeping began, 140 years ago, were from 2015 to 2019, and nine of the 10 hottest years have occurred since 2005, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Atmospheric concentrations of CO2 have been increasing at the rapid pace of two to three parts per million annually, reaching about 415 parts per million (PPM) today — compared with 280 PPM when the Industrial Revolution began. These scientific fundamentals are indisputable, as is the extreme warming taking place in the world’s ice zones, especially at the poles.

Satellite imaging shows that the extent of Arctic Ocean ice has shrunk by 10 percent per decade since 1979. Record warmth in Greenland is now causing its massive ice sheet to shed hundreds of billions of tons a year, raising global sea levels. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet, whose eventual disappearance could raise sea levels by 16 feet, is becoming unstable as air and ocean temperatures rise. Mountain glaciers worldwide, from the Alps to the Himalayas, are melting.

Climate-change skeptics raise a number of arguments that purport to show that the current rates of warming are somehow not related to human activity. One of the most common is that the earth’s climate has undergone cycles of climate change for hundreds of millions of years. That is indeed true. Vast and prolonged outpourings of basaltic lava from inside the planet’s mantle, such as occurred about 250 million years ago in Siberia, can warm the climate by filling the atmosphere with greenhouse gases. For the past 800,000 years, the earth has undergone regular cycles of glaciation and deglaciation roughly every 100,000 years.

These shifts — known as Milankovitch cycles for the Serbian scientist who discovered them — involve changes in the tilt of the earth’s axis that allow more, or less, of the sun’s energy to strike the Northern Hemisphere, which has considerably more heat-absorbing land masses than the Southern Hemisphere. The peak of the most recent glacial period occurred about 22,000 years ago, after which the earth gradually warmed. But now, in fact, the planet should be moving, over tens of thousands of years, into a new Ice Age — not rapidly warming.

Nearly 100 percent of climate scientists say that the only possible explanation for today’s soaring atmospheric concentrations of CO2 and resulting temperature increases — both of which, based on the geological record, have not been seen in tens of millions of years — is human-generated carbon-dioxide emissions.

(For a list of other common climate change-denial talking points, and rebuttals to them, see here.)

What Counts, and What Doesn’t, In Covering Climate Denial

The career of Justin Gillis, who reported on climate change for The New York Times in the early 2010s, tracked — and indeed helped shape — the arc of global-warming coverage in recent years. Gillis wrote an award-winning series of articles called “Temperature Rising,” which explained the science of climate change and chronicled its impacts. Then, in 2014, he was the principal writer of another series, “The Big Fix,” which delved into possible solutions to the climate crisis. He is now writing a book on that subject.

As Gillis’s coverage demonstrates, the climate-change story has shifted from establishing that global warming is unquestionably a human-caused phenomenon to the tale of how those impacts are playing out in many locales and what can be done about it. “You can sort of predict the overall temperature evolution of the planet,” he told me, on the basis of different projections of future CO2 emissions. But as to how exactly that warming is going to change the planet, and how quickly, “there is less clarity.” There is uncertainty, for example, regarding what rising temperatures of the ocean and the air will mean in terms of the number and severity of hurricanes. The role that clouds will play in moderating, or exacerbating, human-driven temperature increases is also a subject of intensive study. How high global sea levels will rise by 2100 — three feet? six feet? — depends on still-uncertain rates of ice sheet melting and collapse.

Responsibly covering this legitimate scientific uncertainty is one challenge for editors and reporters. But reporting on whether human-caused climate change is real is not a matter of debate.

“I’ve drawn a circle on a blackboard in front of students and said, `Within this circle, we have legitimate science going on. There’s a lot of uncertainty within this circle,’” Gillis says. “Then, over on the far right side, I draw another circle and say, `OK, here you have a bunch of crackpots.’ The stupidest of these crackpots say things like, ‘Carbon dioxide is not a greenhouse gas’ or, ‘The planet is not actually warming’ — all this stuff that’s completely nuts. If you’re writing a science story, this can be completely dismissed.

“But what if I’m writing about the politics of climate change? Suddenly these people who are irrelevant to the science are highly relevant to the politics. A third of the U.S. Congress comprises climate deniers, and part of them go about babbling complete nonsense.”

Climate denial has really taken hold in this country, to the point where it is a touchstone of one of our major political parties, and where tens of millions of Americans don’t accept climate change.

Neela Banerjee, supervising climate editor, NPR

Nevertheless, when such people hold office, they have the power to affect policies as crucial as carbon taxes and incentives for renewable energy. Tracking the influence of powerful libertarian and anti-regulatory interests that peddle climate denial — like the Koch Brothers and the Heartland Institute — on politicians and policy is an important part of climate coverage, on the national and local level. (A list of organizations and individuals who fund groups disseminating false and misleading information about climate change can be found at the Union of Concerned Scientists, California’s Office of Planning and Research, and Greenpeace.)

Neela Banerjee, the supervising climate editor at NPR and formerly a reporter at InsideClimate News, says that even though the pseudoscience behind climate-change denial has been discredited, the forces attempting to sow doubt about the reality of global warming still wield influence. “Climate denial has really taken hold in this country, to the point where it is a touchstone of one of our major political parties, and where tens of millions of Americans don’t accept climate change.”

The key to covering climate denial, Banerjee says, is holding corporations, organizations, and politicians accountable: “It pulls back the curtain and tells how it’s affecting our lives.”

At InsideClimate News, Banerjee worked on two series that exposed important instances of climate denial and the influence of the fossil-fuel industry in American politics. The first series showed that well before Exxon became a leading architect and funder of climate-change denial, the company’s scientists and top executives — thanks to studies by its own researchers — fully understood and accepted that burning fossil fuels would harm the climate. The second series showed that for decades, the American Farm Bureau Federation, a major farm lobby, worked, as she put it, “to defeat treaties and regulations to slow global warming, to deny the science in tandem with fossil fuel interests, and to defend business as usual, putting at risk the very farmers it represents.” Given the significant greenhouse-gas emissions associated with agriculture and livestock production, the farm bureau’s stance has been a significant impediment to fighting global warming in the U.S.

“So, if you live in an agricultural state, your state farm bureau could be doing things to address climate change and to prepare their farmers, like implementing crop cover and other steps to address carbon storage and the soil,” says Banerjee. “But if the bureau is still giving money through campaign donations to politicians who deny climate change, then that’s a good accountability story. Which is it? Are you going to help your farmers adapt to or mitigate climate change? Or are you going to elevate people whose policies are going to make the lives of your farmers even worse?”

Kate Sheppard, a senior enterprise editor at HuffPost, who previously covered climate change and the environment for Mother Jones and Grist, cited another example that reporters at HuffPost published in 2020: how misinformation about climate change has made its way into public-school textbooks. As part of a nine-story series, “Are We Ready?,” HuffPost ran an article that reviewed 32 middle- and high-school textbooks and digital curricula being used in Florida, Texas, Oklahoma, and California.

The article cited numerous instances of false or misleading information that were included in widely used textbooks issued by major publishers, such as Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and McGraw Hill. Twelve of the textbooks contained statements that were erroneous or misleading, four did not discuss global warming at all, and others “downplayed the scientific consensus that human activities are causing the current climate crisis.” The Texas State Board of Education, known for its record of anti-science views on evolution and global warming, has an especially egregious record of approving textbooks that cast doubt on climate science.

Among the assertions in the 32 textbooks HuffPost reviewed were that climate change “is one of the most debated issues in modern science”; that “scientists hypothesize” that rising CO2 emissions have “contributed to the recent rise in global temperature”; and that “some critics say that this warming is just part of the Earth’s natural cycle.” Those are common tropes put out by climate-change-denying groups, and all of them are false. There is virtually no debate in the scientific community over whether human-caused emissions are the overwhelming reason for today’s planetary warming. The greenhouse effect is not a hypothesis; it is an established principle of physics. And there is near-unanimous agreement among climate scientists that the climate change now sweeping the globe is not part of a natural warming cycle, but rather the result of enormous quantities of carbon dioxide being pumped into the atmosphere by human activities.

“It’s important to know who’s behind this denial and what their motivations are, ideological and financial,” says Sheppard. “What kind of influence are they having, and how are they reaching people out in the world?”