The Fact-Checking Process

By Brooke Borel / 5 minute read

Fact-checking may seem straightforward, but you might be surprised at how many “facts” a fact-checker will see in a story. Below, download the six-paragraph passage from an Undark story and underline every fact. How many facts do you find?

Once you’ve done that, download my “answer” sheet, showing every fact I’ve found. Did you get them all?

My guess is you might have missed a few. But, with a proper fact-checking process, you can ensure that your stories are well-checked and error-free. Ideally, that process would look more or less like this, which is based on the magazine model:

Step 1: The Writer and Editor Finalize the Story

This isn’t the absolute final version that will be published, of course. But when it comes to the overall structure and sourcing, this is the version that both the writer and editor feel is ready for scrutiny. In other words, they don’t plan to keep tinkering with different ledes, move sections around, add a lot of reporting, or do any other major story surgery.

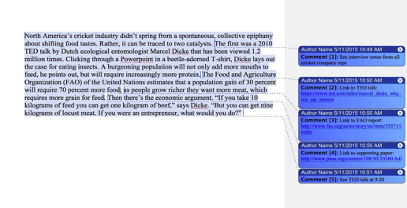

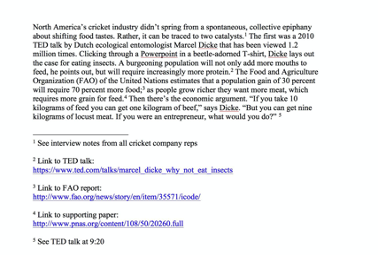

Step 2: The Writer Annotates a Copy of the Story and Sends It to the Fact-Checker

In order to help the fact-checking process move smoothly, it’s vital for the writer to give the checker a clear road map of the reporting. The first step is to annotate a copy of the near-final story. Most drafts will appear in either Microsoft Word or Google Docs, which means the writer has two choices for annotations: footnotes and comments. Either way, the writer will use those tools to cite every source for every fact: contact information for experts or eyewitnesses; descriptions and file names for interview recordings, transcripts, journal articles, and email correspondence; titles of books or other print sources; and links to key websites (although screenshots or PDFs are also recommended, since websites can change).

One of my favorite fact-checking strategies is to save PDFs of the websites I visit for a story in a single file, and to add comments (bubbles) in the text of the story with chunks of the related facts from those websites/pdfs.

Roxanne Khamsi, freelance science journalist

The more detail the better. For instance, if a quote came from an interview recording, the writer should include the timestamp. If information came from a book, the writer should provide relevant page numbers.

Step 3: The Writer Provides the Fact-Checker With Sources

The next step is to identify the sourcing. For most sources, the writer should provide files that correspond to the citations in the annotation (with the exception being human sources; for those, contact information is fine). If the material isn’t particularly sensitive, the writer could send it by email or with a file-sharing service such as Dropbox. If the sourcing includes sensitive information, the writer may want to use password protection and/or encryption. And if the material is especially sensitive — for example, if it includes documents and identification from a whistle blower — the writer may want to send a hard drive or laptop and request that the files not be transferred to a computer with an internet connection.

Step 4: The Fact-Checker Fact-Checks

The fact-checker reads through the piece at least once, then goes through it again line-by-line, checking each fact against its source. This may require phone calls with experts and other people who appear in the story or in the writer’s notes. The fact-checker also assesses the quality of the back-up material and may look for new sources as needed.

Step 5: The Fact-Checker Proposes Changes

The fact-checker presents a list of proposed changes to the writer, the editor, or both. At many news outlets, the fact-checker will simply use tracked changes and comments in Microsoft Word or Google Docs to flag the changes and provide context. (Exception: If the fact-checker runs into major problems, such as errors that dissolve the premise of a story, or evidence of plagiarism, those shouldn’t be saved until the final report. They should go to the editor immediately.)

Step 6: Review

The editor or writer — or, more likely, both — will review the proposed changes. There may be some back-and-forth with the fact-checker, both to negotiate precise wording and to collectively evaluate different sources. For instance, a fact-checker may push for a word that is more technically correct, while a writer may advocate for something that doesn’t come across as jargon, and the team will have to decide what word best serves the reader. Or the writer may have used one study to support a point, while the fact-checker may have found other solid research that contradicts it — here, the team will have to figure out how best to reflect this uncertainty in the text, or whether some of the studies are not worth citing, perhaps, for example, because their authors have serious conflicts of interest.

Step 7: Make Changes

Once everyone is in agreement on the facts, either the fact-checker or the editor makes the final changes in the document. But if there are disagreements, it is typically the editor’s job to make the final call.

Remember that you are working on behalf of both the reader and the writer. You want to be sure the reader sees correct information, but you are also making sure the writer can tell a compelling story, so suggest accurate edits that are true to the writer’s voice.

Brad Scriber, deputy research director, National Geographic

The Newspaper and Hybrid Models

The newspaper model may follow an abbreviated version of the lengthier magazine model. But, of course, this model doesn’t involve a dedicated fact-checker. Here, the writer and editor typically finalize a story. During that process, the editor should push back on various claims and sources to make sure the writer is using solid evidence. Then it’s passed on to a copy editor, who may also do a light fact-check for basic information.

To help build fact-checking into the system, the writer can add steps to the reporting and writing process. For instance, a writer should always make every effort to verify information with good sources before putting it in a story — especially if that information is key to the premise. Second, a writer should set aside time after the story is finished to go back through it line-by-line and double-check the sourcing for each fact.

The hybrid model combines the briefer newspaper process for short or time-sensitive pieces and the in-depth magazine model for more-complex pieces, including long-form, narratives, and legally sensitive stories.

Fact-Checking Best Practices

Fact-checking works best when you have a consistent and clear editorial process for your staff and freelancers.

- Create a work flow — including clear stages and responsibilities for editing, top-editing, fact-checking, and copy editing. All stories should go through this process.

- Avoid letting journalists, sources, editors, or fact-checkers bend the rules or the process.

- Always make sure your journalist has strong evidence for big claims, which include:

- Sweeping “scientists say” statements.

- Scientific findings that counter the majority of existing relevant studies.

- Information that suggests, or outright says, that someone committed a crime, ethical breach, or anything else that could get you sued for libel if it proves to be wrong.

- Information about medical devices, diets, and any other product or practice that could harm a reader if it proves to be wrong or misleading.

- Create checklists for reporters that they can tape to their computer screens, reminding them to always double-check sourcing for:

- Spelling of names and places

- Titles and affiliations

- Ages (be sure to check if a source will have a birthday before publication)

- Gender and preferred pronouns

- Dates

- Basic numbers and statistics

- Geographical locations

- Common typos (should that be millions or billions?)

- And any other quick, easy facts that are easy to double-check — and easy to get wrong