Introduction

By Laura Helmuth / 2 minute read

Journalism is having a reckoning. People inside and outside the business are re-examining the tension between truth and objectivity, questioning whose voices we amplify and don’t, warning about the dangers of publishing both sides of a controversy when both sides aren’t supported by evidence, and learning when to call racism racism and a lie a lie. The reckoning accelerated with criticism of coverage of the 2016 presidential campaign and of the Trump administration, and it has become more urgent with the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement for social justice.

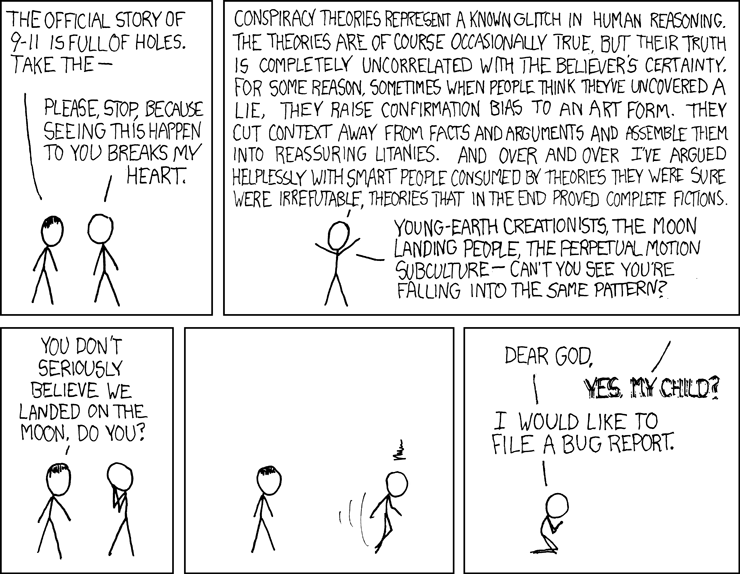

Science journalists have been grappling with these questions for a long time, and other areas of journalism could learn from our experiences. Good science stories don’t air both sides of a debate when only one is correct: We don’t include creationists in a story about evolution, climate-science skeptics in a story about climate change, or antivaccine activists in a story about vaccines. And when we cover creationism, science denial, or antivaccine activists, we make it clear that those views are contrary to the evidence. We call a conspiracy theory a conspiracy theory.

We evaluate the relevance of someone’s expertise, and we don’t trust people solely on the basis of their credentials. An expert in one field might be very confident in a mistaken notion about another field, as we’ve seen with some amateur epidemiologists who have made bold predictions about the coronavirus pandemic. We generally know better than to quote a Nobel laureate saying something bombastic about a topic outside his or her area of expertise. When a publication does make an error in judgment, such as when The New York Times quoted James Watson (co-discoverer of the structure of DNA) saying that another scientist “is going to cure cancer in two years” — that was in 1998 — the rest of us try to learn from it.

That said, controversy is a powerful elixir: It can draw the attention of people who don’t usually follow science but who like a good brawl. Controversies often involve passionate characters who offer up arresting quotes. Presenting a science story as a controversy can help get attention within a publication as well — it’s a framing that top editors and the guardians of the front page or home page understand. But like nuclear power, you should use controversy for good, not evil, and be careful of spills.

This chapter will cover how to tell the difference between a false controversy, a policy controversy, and a science controversy. It will examine issues of fairness, false hope, and how to protect yourself and your publication and writers from lawsuits. And it will have practical advice about how to constructively use controversy to get attention in a crowded news environment.