Measuring Success

By Katie Fleeman / 10 minute read

Analytics

Web metrics and social-media data can be powerful tools for assessing what’s resonating with your audience – or they can be a confusing and potentially misleading jumble of numbers.

Analytics are not intended to replace editorial judgment. Rather, they should help guide decisions when you are faced with limited resources or several equally good choices. Here are some ways to make use of metrics:

- Identify what’s important. Deciding what numbers you want to look at will depend on broader strategic goals – editorial, audience, business. Your publication might be interested in which types of stories drive subscriptions, which ones attract repeat users, or what stories get the most organic social-media play. Focus on those figures, rather than “vanity” metrics, like what stories drove the most clicks. Clicks are nice, but subscriptions pay the bills. For more, read about vanity metrics and how to identify them in Tableau.

- Stakeholder buy-in is crucial. Lots of people can have a role to play in understanding and making use of the analytics. As an editor, make sure that you understand what insights and conclusions you can and cannot draw from the numbers, and that everyone agrees on those guidelines.

- Look for simple nuggets first. Analytics are easier when you break them down into manageable chunks that can be built up into a knowledge corpus. For example, you might ask simple questions like:

- What is the best time of day for our Facebook posts?

- What hashtags correlate with the biggest reach?

- What headline format (or length) drives the highest click-through rate?

- Are there any evergreen stories that consistently drive SEO traffic? (And do they have links back to newer, relevant stories?)

- Set up simple systems. It is easy to set up small-scale processes — like having someone hand-post Twitter messages — and hard to maintain them. Automate whenever possible, and try to find ways to make recurring reports simple to put together and send.

- Be mindful of morale. Not all metrics will show happy news. Some stories don’t resonate, some strategies don’t work. You don’t want to obfuscate or hold back on sharing an unpopular stat. Rather, develop good bedside manner. To that end:

- Don’t lay blame. It’s not about someone doing something wrong, it’s about the lesson that can be learned.

- Highlight and learn from success stories; don’t focus on the failures. That’s not to say failures should be ignored; indeed, interrogate them and learn lessons from them. But share the success stories and explain why they are successful. People will naturally work to replicate what works and is praised.

Here are three case studies that demonstrate how those concepts can be put into practice:

Case Study 1: Using Analytics When Assigning Stories at Science News

Understanding your audience’s interests can help you figure out the best way to use your resources. Mike Denison, audience-engagement editor at Science News, explains:

I noted in a quarterly report that we covered a lot of spacecraft launches, and those did nothing for us. Low traffic, low engaged time, wasn’t exactly inspiring a ton of reader feedback. [Those are] really quick-turnaround, high-pressure stories. It’s a good bit of work and planning for not very much reward. Pretty soon after that meeting, our assignment editor [said], let’s not bother writing up launches, just tweet about it and let the brand account retweet you. Let’s focus our energy elsewhere, unless it’s a really big deal. I think that was a good [example of] using analytics to stop doing something. It wasn’t like our astronomy writer suddenly had nothing to cover anymore. They just had a little bit more bandwidth for bigger stories that would resonate more with readers.

Case Study 2: Using User-Generated Content to Engage Audiences: #AgarArt

How can art (and audience participation) engage people in science? Chaseedaw Giles, creator of the American Society for Microbiology’s annual #AgarArt contest, explains how beautiful images made of microbes and concocted in petri dishes capture the public’s attention:

The goal was to communicate science to the public and bring more awareness to the field of microbiology. It really got the public into microbiology because it was art. It showed how microbes can be really beautiful. Even though they’re germs, they can be really beautiful. To roll it out, we created a web page on our site to announce the contest and sent out a press release to our members. We used our social-media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) to promote the contest, and we created an “agar art” art gallery at our annual meeting, where we display current and past contest winners’ submissions. [Advice for someone who wants to launch a project like this]: If you manage a social-media channel, look for trends in the content that you share. What seems to get people the most engaged? Once you find that, explore it. Even if you don’t manage social media, search for the content you are trying to promote on social media. Is there a niche that needs to be filled? Is there content already there, but it’s not organized in a way that people can easily access it? That’s what we did with agar art. The content was there, and people really liked it, but it wasn’t organized in one place, and didn’t have any cohesive branding tying it all together. That’s when I decided to turn it into an art contest that went global.

Case Study 3: Catching Misuse of Older Stories at The Scientist

Content can take on a life of its own — and sometimes be misused. Paying close attention to your analytics can uncover these potential and unintentional bouts of misinformation. Shawna Williams, a senior editor at The Scientist, explains how archival content can take on new life:

One interesting case we've had recently is this article that we published in 2015, about a coronavirus that was made in the lab and sparked controversy at the time. If you look at our homepage, it's been on the right trending columns since January [2020]. And we know that this is up there because people are spreading it around and saying, look, this virus [SARS-CoV-2] was made in a lab — either it escaped accidentally, or it was a bio weapon that was made on purpose. And that is, as far as we know [in April 2020], not the case at all. We did end up doing a story on "Is there any evidence that this virus originated in the lab?", and we put a link to it at the top of that article. But, of course, the social-media preview doesn't indicate that, and also doesn't indicate that this is an article from 2015. There's nothing wrong with the [original] article. It's completely accurate. But five years later, it's being used in a way that we never anticipated.

Lisa Winter, social-media editor at The Scientist, describes how they came to realize the story was being misused:

[The news director] Kerry Grens keeps a pretty close eye on the Google Analytics. And at first it was just like, oh, that's weird. The story is getting picked up. And then the emails started coming in from all of these wild conspiracy theorists, and it was getting posted on these blogs — with Google Analytics, you can see the source of where the link was clicked. And it was really kind of wild. And it was a debate: Do we even need to say this? Because we can't go following up every single article that might get posted someplace that we don't agree with, and we can't make a statement on every single story. But that one just got so huge, so fast, that it required a little clarification.

Read more: In addition to writing a new story, The Scientist’s editor in chief wrote about the experience in “Going Viral for the Wrong Reasons.”

Comment Sections

Opinions vary widely when it comes to comment sections. Should you heavily moderate, or treat them like a public square? Should you jump in to address misinformation, or rely on other readers to correct them? Will they offer valuable insight, or abuse one another (and you)?

A few considerations:

- Define the purpose of the comment section: Cultivate a community? Foster direct relationships with readers?

- Develop a clear commenting policy: This will give you something to point to if you need to delete posts or ban a user.

- Realistically evaluate your bandwidth: Comment moderation can be time-consuming, especially if you have high volume.

The Coral Project has compiled numerous guides and resources for moderation and creating community, including a step-by-step guide for creating your community, from defining strategy to sustaining community culture. (There is also a printable workbook version.)

The section on codes of conduct provides a robust set of questions for you to consider while developing your community guidelines, along with examples and a recommended structure for writing out the policy.

When two science-focused websites underwent a redesign, they took two approaches to comments, based on their experiences with their audiences, as described below:

Case Study 1: Yale Environment 360

Katherine Bagley, managing editor, keeps comments open because the audience does a good job of regulating itself.

Our readers are pretty good at moderating the communities. If somebody is being a jerk, our other readers will very quickly step in. Or if we get trolled — which happens a lot with environmental sites, especially on any climate-change-related posts — our readers will often jump in and defend. We will watch those things, but we'll jump in only under extreme circumstances. We have our writers monitor the comments section under their stories for a couple of days after stories are posted. Occasionally, if they see the need, or if they want to, they'll respond. And I think that generates some interest [and shows that] we're paying attention to what they're saying. We did a website redesign three years ago, and [whether or not to keep the comment section] was a really big discussion. We kept it open because [our audience] really leave[s] thoughtful, in-depth comments that generate discussion. We find snarky comments on social networks, but if people are coming to our stories and really commenting at the bottom of them — you have to click on a button to open it — we find that the comments really do generate good discussion. I learn from them, too. And it's good for us to hear the different angles that people come away from a story with.

Case Study 2: Science News

Mike Denison, audience-engagement editor, describes how the amount of work required to monitor their comments, and the general low level of discourse, led them to end comments and refer readers to a feedback e-mail address.

Having a free-for-all open forum leads an organization to make a lot of really difficult decisions of either having a lot of comments present that are not in line with organizational mission or [sense of] decency — or you had to spend a lot of time moderating the comments or trying to create a discussion you'd look for. We tried to "have our cake and eat it too" in that regard at Science News, and it led to me deleting a lot of comments, to the point that serial commenters would start saying things like, "Shh, be careful, Mike's gonna delete all this." And that's not good for anybody. So, when we overhauled our website in 2019, we thought this was a natural point to kill the comment section. (And also, on a technical level, comment sections slow your page-load time.) Where previously at the bottom of an article would be a comment section, [now there is] just a box, telling readers to email us at feedback@sciencenews.org. We set up different shifts for people who were going to monitor the feedback emails and respond to them where appropriate.

Polls and Calls for Feedback

Polls and call-outs embedded in your stories can provide fertile ground for collecting directed feedback and questions from your readers. How these are set up and deployed will vary on the basis of your goals.

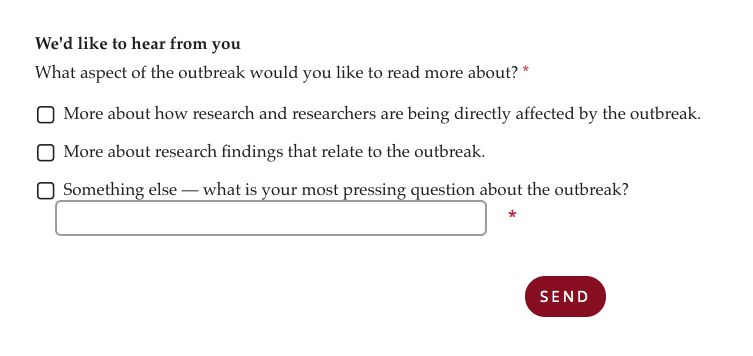

At Science Friday, producers were working on a local-climate-change project in which they solicited reader feedback. Doing so allowed them to hear from people all around the country. At Nature, producers use polls to get feedback on what to cover as well as ways to gauge reader interest. Here are three examples in which Nature used feedback forms to learn what readers wanted to see more of:

Steering Covid-19 Coverage

- Goal: Guide coverage of Covid-19 so that resources could be used most effectively and wisely, and content would appeal to the target audience.

- Approach: Early on in the outbreak, Nature embedded a call-out in a few stories asking readers what they wanted to know more about — the impact of the outbreak on researchers, the research findings, or something else.

- Outcome: Based on reader responses, Nature‘s editors focused on assigning stories covering continuing research.

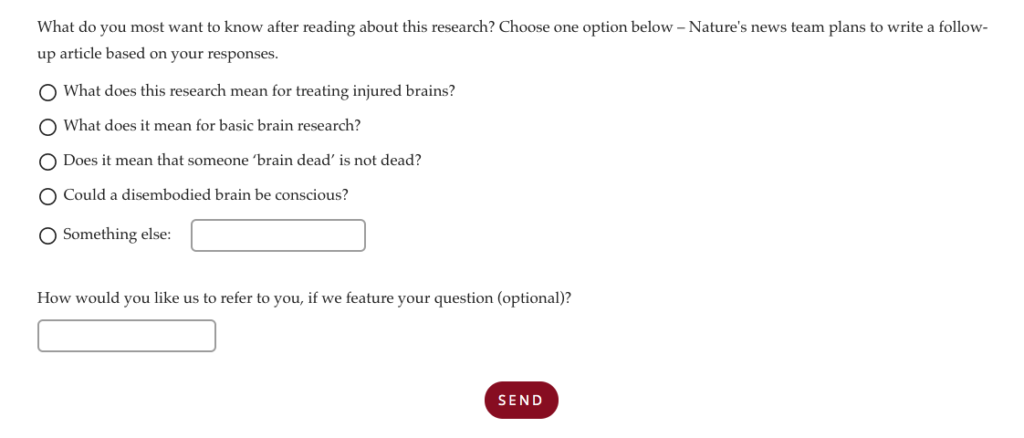

Gathering Questions for Follow-Up Stories

- Goal: They were covering a big story — “Pig brains kept alive outside body for hours after death” — and knew that the initial article couldn’t cover everything, so they wanted to discern what additional information their core audience of scientists wants to know about a major scientific development.

- Approach: They included a widget for responses, but placed it deliberately low on the page, so less-engaged (and theoretically more general) readers would be less likely to see it. The poll itself included prompts to guide respondents toward the types of questions Nature wanted to answer (e.g., “What does this mean for basic brain research?”)

- Outcome: Manageable volume of relevant questions, and a resulting article.

They don’t need to be bells and whistles. Some of this is very basic stuff. It’s just taking your more traditional journalistic approaches and applying them in a more digital way, or several magnitudes bigger.

Anna Jay, chief editor, digital and engagement, Nature

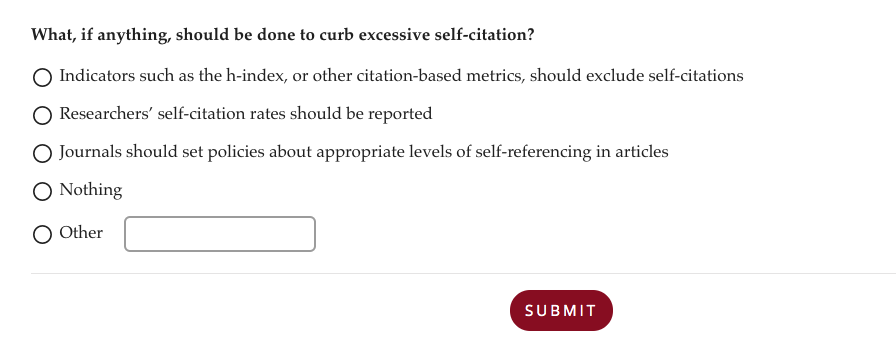

Checking Preconceived Notions

- Goal: Gauge their community’s response to a news story that they anticipated would be popular both with the core audience of scientists and to a broader base.

- Approach: On the news story, “Hundreds of extreme self-citing scientists revealed in new database,” they included the above poll; the results were shown immediately, so readers could see the sentiments of their peers.

- Outcome: Nature published an editorial based on the responses. It also included a static graphic of the interactive poll in the original article, to provide that information for future readers. (By including the static graphic, they pre-emptively prevented the interactive poll from breaking if they ever switch survey tools.)

Fostering Trust With the Transparency Project and Science News

The Transparency project is a collaboration between Science News and News Co/Lab, a digital-media-literacy initiative at Arizona State University. The content consists of sidebars on stories covering controversial or politically charged topics, such as vaccine hesitation and industry-funded studies. Why did Science News report on this? What steps did editors take to be fair or avoid bias? What questions were not asked? At the end of the sidebar, readers are invited to take a quick survey about their perceptions of Science News’s trustworthiness.

The idea was that if we showed readers that we’d done our homework, that would put to bed any potential ideas that we were acting maliciously or following some other ulterior financial motive or any other kind of ulterior motive.

Mike Denison, Audience-Engagement Editor, Science News

If you do choose to embed feedback calls to action or polls, here are a few tips as well as pitfalls to avoid:

- Think through why you’re including a call-out. Having a clear idea of what you want to get out of soliciting reader responses will help with making call-outs more precise and actionable.

- Determine a timeline. Set an end date. Or, if you leave a poll open indefinitely, make sure you have the resources to monitor it. (Bonus: If you’re using a third-party tool, you’re less likely to end up with broken widgets around your site.)

- Be upfront about how responses may be used and tell readers what they will get from responding. Will they immediately see answers from their peers? Will their responses help shape future coverage? If so, say so.

- Place call-outs lower in a story, to filter for more-engaged readers. Instead of gut reactions based on a headline, responses will come from those who made it through most or all of the story.

- Put yourself in the shoes of someone trying to respond. People will drop out if it’s too onerous to complete.

- Keep it in perspective. Embedded polls on your site do not carry any statistical weight as studies, so if you use them as fodder for stories, be sure to make that clear. Contextualize the results appropriately, as was done in this story: “Two-thirds of researchers report ‘pressure to cite’ in Nature poll.”