Telling the Right Story

By Rachel Feltman / 10 minute read

Writing about science as a great story begins not with line edits, but at the beginning of the assigning process. The first question to ask yourself is whether this science news is worth covering. The next is how your reporter should cover it. Having the right conversations with a writer in the earliest stages of reporting can help ensure that you receive copy with the potential to become a great story.

First, consider — and ask your writer to justify — the need for this particular article.

Here are some less-than-ideal reasons to assign a story:

- It’s trending online. It is, of course, tempting — and sometimes necessary — to chase the algorithm-assisted traffic bumps that can result from grabbing onto a story that’s trending on Google or Apple News. While that is a fine way to find stories to consider covering, news-curation platforms have a bad track record when it comes to serving up good and important science news. While some social news feeds have quality-control editors or spotters on the lookout for stories to include, the question of what rises to the top is largely dictated by algorithms — computer script designed to pluck out articles that are likely to be clicked on, and then to continue promoting those links and ones like them to feed off of click success. Google and Facebook have not entered the same endlessly negative feedback loop as, say, YouTube, which has become a hotbed of radicalized misinformation in the effort to attract eyeballs. But in addition to often relying on racist, sexist, or otherwise problematic human viewpoints in deciding what news is worth sharing, these sorts of semi-automated feeds are often just not very smart. I have, on more than one occasion, seen Google News share an unscrupulous headline about alien life on Mars as one of its top science stories.

It’s easy to spot a tabloid article about how there might be little rodents on Mars as an obvious falsehood, but not everything that a news-feed curator or algorithm mistakenly elevates will be so obviously false. Misleading headlines are a much more common problem, as are fairly unimportant studies and stories that rose to the top simply because something about them sounds exciting. For example, most studies on nutrition are misleading, or represent only an incremental change in medical advice. Actually understanding how food affects health is difficult to track and even harder to translate into widely applicable advice. But because most people drink coffee and care about how long they’ll live, a study claiming to show that coffee adds to or subtracts from projected lifespan is always going to trend high.

As an editor, you should never assume that something is worth elevating just because it’s trending. Dig deeper before you assign it. Ask why it’s caught the attention of so many people, and see what various experts are saying about the news. Ask your writer if the story can be moved forward.

- It’s embargoed. Getting access to embargoed journal articles — either through a service like EurekAlert or directly from a publication like Nature — is a good way to stay abreast of current and forthcoming science news. Many scientific studies are released “under embargo,” which means that journalists and editors have a chance to look at their findings (and perhaps their data) before the news goes public. However, scientific institutions can and do use the embargo system to their own benefit. Because an embargo gives journalistic publications more time to report before the news can end up trending on Google or Facebook, these studies are often viewed as more serious and more worthy of our attention. But plenty of good and important pieces of science news are sent out to journalists at the same time the findings go public, and most embargoed studies are far from groundbreaking. The existence of an embargo is not, in and of itself, a cue that science news is particularly important.

- The press release says it’s a big deal. If the White House sent out a press release trumpeting how amazing a particular presidential initiative was going to be for the country, you wouldn’t just seek to confirm the stated facts. As a skeptical editor, you would question the way the administration was framing its actions, and ask yourself what it might serve to gain from spreading that narrative. It’s obvious, in this scenario, that the press officer is pushing a particular agenda — perhaps not a malicious or even misleading agenda, but that’s for your reporter to suss out. Science press releases are the same: They are crafted by entities, like universities and drug companies, that stand to gain from widespread praise of the work described therein. In many cases, a press release will overstate the importance of a scientific finding or even misrepresent the facts. A thrilling press release often turns out to be science fiction; you should never lean on the narrative presented by a press officer in your quest to assign and craft a compelling story.

Here are some good reasons to assign a story:

- Scientists (other than the ones who did the study) seem excited. Just as you must assume that the people writing press releases have an agenda, you must also recognize that scientists have a bias when it comes to studies they’re involved in. No amount of excitement from a study report’s author, however genuine, should be taken as evidence that the story is particularly novel or important. But that doesn’t mean excitement within the scientific community should be discounted. This is where it becomes helpful to cultivate a wide array of scientific sources to keep in touch with and follow on social media: Watching for a generally enthusiastic reaction about new research can clue you in to findings that are actually a big deal.

- It concerns issues that will seriously impact peoples’ lives (even if those people aren’t your readers). One of the most important jobs a science editor has is elevating research and news that readers might not realize will affect the world around them. Sometimes these topics are obvious — climate change is altering the fabric of the earth, even though many individuals in wealthy countries don’t see clear effects of it every day. Other topics are easier to ignore: A study on how palm-oil production is affecting wildlife diversity in Borneo may not seem immediately interesting to your readers, even if you understand that it’s a serious issue. But their shopping habits are likely to contribute to the problem — poorly sourced palm oil is in countless products sold across America. For a story like this, the reporter and editor must explain not just what the problem is and whom it will hurt, but also why the reader — presumably not in immediate danger — should care. These stories are under-covered but quite valuable.

- It explains something being discussed in the news, or uses a current event as an opportunity to explain a scientific concept. When “The Dress” and “Yanny vs. Laurel” went viral, these digital illusions sparked online debates and countless memes. Science had a place in the conversation: Both of these seemingly silly internet arguments could be explained by talking about the quirks and limits of human perception. If everyone is talking about the same thing, editors should ask themselves what science stories could ride the resulting traffic wave. This can be overdone — you don’t need to explain “the science of” every single superhero movie, given the fact that most of them contain little actual “science” — but it’s certainly worth soliciting pitches that take a sideways look at big news events. You can also use current events to get readers interested in bizarre but informative science questions, like how much sweat comes out of a single Super Bowl.

- Lots of publications are getting something very wrong. Sometimes a debunk — in which your reporter explains what other publications or the general public are getting wrong about a widely -shared story — can provide a valuable service. If the story is trending on news algorithms or social-media platforms, debunks also have a shot at surfing a big wave of traffic. Consider this article on dolphin perception, which I wrote after looking into a story being shared on many science and tech websites. Googling the source of the press release and reaching out for comment made it clear that the widely shared narrative was untrue.

One note of caution: It’s important not to “debunk” articles that are not getting significant attention or convincing lots of people of something untrue. Doing so can serve to elevate dangerous mistruths to an even larger audience. For instance, Popular Science may not have chosen to report on sellers of bleach as a medical treatment if the promoters had done business only in small, private Facebook groups. But when the practice was empowered by a statement made by the president of the United States, the claims had a large enough audience to justify debunking.

Once you are confident that this topic is worthwhile, the next step is figuring out what kind of approach and treatment a story warrants. Not every story will shine in the same outlet, or with the same editorial treatment.

Is It a Story?

“I happen to think that if it’s important science and there’s a news hook, there’s always a way to make the story compelling,” says Maddie Stone, a freelance science writer and founding editor of Earther, a website of nature news.

She goes on:

I think it comes down to figuring out, first and foremost, who the audience is. If it’s a story about a new medical device that is a big deal for individuals with a rare condition but won’t affect anyone else, that’s probably better suited for a medical news outlet than the NYT science section. If the science is important and impacts everyone but the technical details are very dry, then it’s about getting the “why does this matter to me” front-and-center.

There are several questions you should ask in order to determine whether a pitch is a compelling story.

Does this article feature life-or-death information?

Some pieces of science news — especially in the age of global pandemics like Covid-19 — are simply crucial for the health and wellness of the general population. While the era of digital news means that all stories must be presented in an interesting and engaging way, getting potentially lifesaving information to your readers quickly and efficiently is more important than weaving a stunning tale for them to enjoy.

Popular Science has used several story rubrics designed to push out essential information on Covid-19, including weekly roundups of new and important news, and posts with running updates on death tolls and medical advice. It publishes these articles, which are reported for accuracy but written without much concern for narrative or “story,” in addition to more compelling and gripping pieces on similar topics. Sometimes a short and efficient piece of science news should stay exactly that.

The reverse-pyramid structure is your best friend in these circumstances, particularly when readers may have a hard time understanding why this reporting is so vital. A snappy headline followed by a simple, declarative lede will make sure that readers understand what they’re about to read. You should make sure to quickly present a nut graf that gets at the crux of the importance of the scientific finding. From there, you can add whatever additional information and context the reader might need.

Consider these two (made-up) examples:

She was sure it was just allergies—and then she lost her sense of taste

Dolly Jones has always prided herself on possessing a sophisticated palate. The 53-year-old restaurateur and Brooklyn native cheerfully recalls traveling “from Thailand to Tennessee” to gather inspiration for her Michelin-starred Williamsburg Dolly’s House, which features fanciful fusion dishes such as congee-style shrimp and grits and bulgogi pulled pork sandwiches. But her reveries on past culinary adventures now carry a tinge of regret: For the past two weeks, Jones has been unable to taste even the most powerful of flavors.

“I’ve tried everything from sprinkling cayenne in my chicken soup to chewing on sprigs of mint,” she says. “It’s like my taste buds have gone to sleep.”

“I keep trying to remind myself that being able to taste shouldn’t be my biggest concern,” she adds with a sigh. “But it’s hard to worry about having coronavirus when I see my life’s work flashing before my eyes.”

Dolly’s story is, no doubt, a compelling narrative to follow in exploring the science behind a new and intriguing Covid-19 symptom, and you might very well decide that this feature is worth assigning. But when experts noted that loss of taste is a new sign of Covid-19, readers didn’t need flouncy ledes about foodies. They needed to know to be on the lookout for this unexpected sign of infection.

Here’s a simpler and more effective way to present that information:

Scientists identify a surprising early warning sign for Covid-19

Researchers are now saying that Covid-19 patients can exhibit a more striking symptom than dry cough or fever: They can also lose their ability to smell or taste.

While more research is needed to understand the exact mechanism of this bizarre symptom, experts warn that new and sudden changes in one’s ability to recognize odors and flavors could indicate infection with the virus that causes Covid-19. People who experience this phenomenon should self-isolate from family and friends to avoid spreading the contagion, even if they otherwise feel fine.

From there, this structure can unfold to provide context on where this symptom might have come from, and what readers should do if they suspect they have the disease. Both of these article structures are valid, even though one clearly presents a more compelling story than the other. And in this particular case, the latter — and less engaging — example is probably the one your publication should put out first.

Your science story may not even need to exist as a story; once a week, Popular Science editors solicit questions on Covid-19 from our Twitter followers and answer them live. Some of these answers could have been written out as full stories, and some of them eventually are. But to best serve readers, the magazine chooses to give them the answers they’re looking for in a free, instantaneous fashion.

Is humor appropriate?

Not every story is about a pandemic, and not every science story needs to be serious. One should never try to force one’s way into humor, but as an editor, you can and should give your reporters the freedom to have fun with science news. Are there puns to be made? Cheeky innuendos?

I have, on numerous occasions (like here and here) written or assigned stories on scientific findings about the planet Uranus that lean heavily on puns and double entendres. I would never write a story about a deadly pandemic that relied on butt jokes, but snickering at a distant planet’s expense is about as harmless as fun can get. And guess what: Those stories have gotten a lot of people to care about new scientific findings.

Similar nuggets of fun can be found all over the world of health and science. Allowing your writer to take on a silly tone can be the key to getting readers excited about obscure or esoteric science. There is nothing inherently dirty or low-brow about creating accessible, relatable, and enjoyable content.

Is there too much information for a single, streamlined piece of written content?

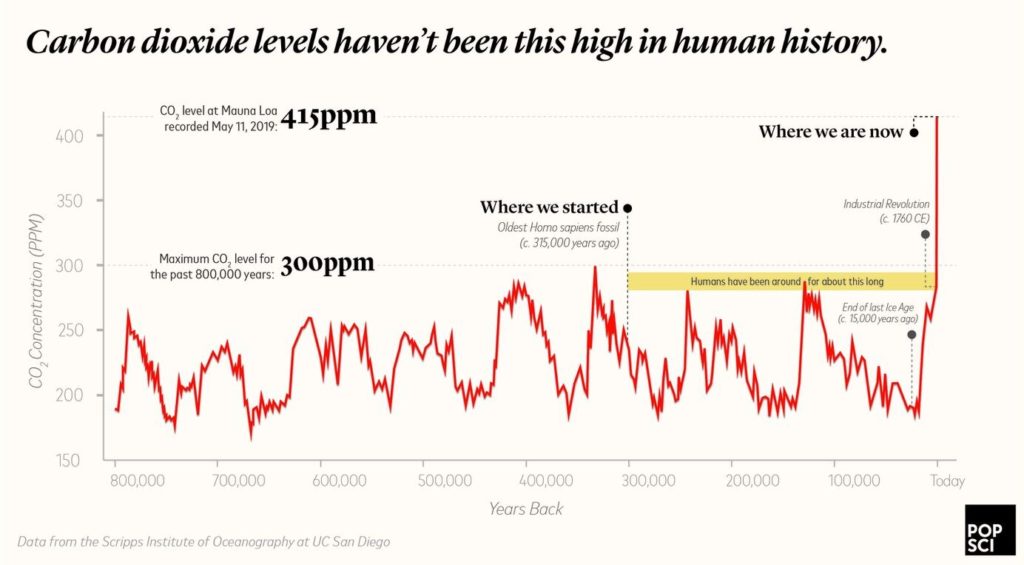

Like any other story, a piece of science news can evolve to take many forms — audio, video, PowerPoint, and so on. Consider whether the facts and figures your writer would have to cram into the text could be presented in a better way. Would infographics or even simple charts be helpful to the reader? These might end up replacing large blocks of what would otherwise be inscrutable text.

Consider the simple but compelling graphic above, which expresses complex data on climate change much more quickly than text can — and was shared widely on social media. You might also create an informational package with different types of rubrics and formats. An opening essay followed by timelines, charts, and short blurbs could be far more effective than a narrative feature.

If you feel it would be impossible to get all of the necessary facts and figures and context into a streamlined story, you might be right — but that’s not an excuse for leaving them out entirely. Sidebars, section headers, and infographics are your friends.