Introduction

By Neel V. Patel / 2 minute read

“Popular science” is generally taken to mean the communication of science to a lay audience. Now, in part because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the term has become far more entwined with daily journalism.

“We’re in a weird transition time where science journalism is just journalism now,” says Yasmin Tayag, a science journalist and former editor of Medium’s science-and-tech publication, OneZero. “Everyone is reading about science all the time because of the pandemic.”

It’s common these days to see science stories front and center on the home pages of national news media, side by side with stories about politics or world affairs. Soon after the coronavirus became international news, it was no longer unusual to hear the average person drop terms like “spike protein” and “cytokine storm” in normal conversation. A public ravenous for information on how to protect themselves and their loved ones from a little-understood disease, and eager to understand what was coming next, helped fuel coverage.

Meanwhile, other scientific topics — climate change, artificial intelligence, the search for exoplanets — have had their own surges in public interest and news coverage.

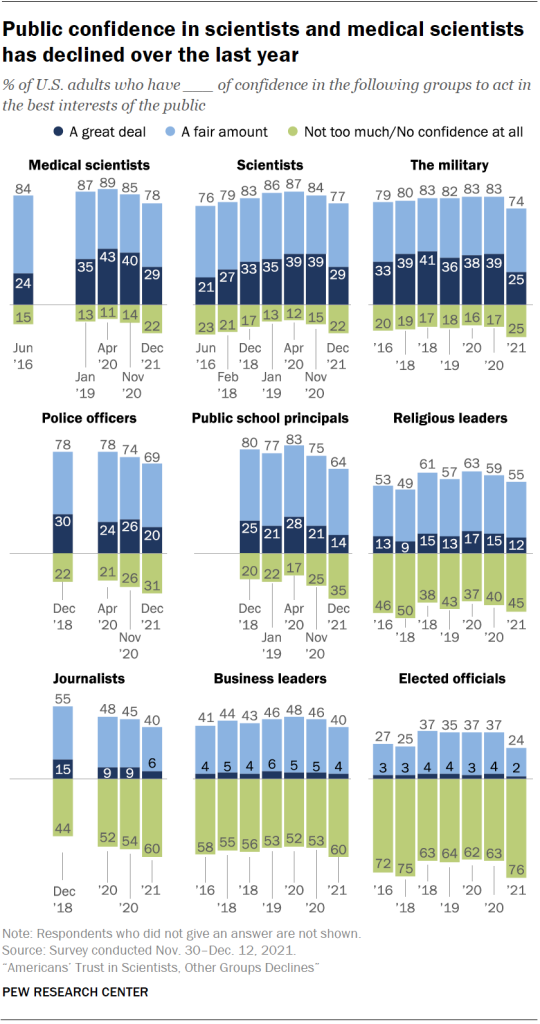

Yet, even though science stories are now more common in mainstream news, we often hear members of the public express ambivalent feelings about science, or even intimidation and aversion. According to a Pew Research Center report released in 2022, from November 2020 to December 2021 the share of Americans who felt a “fair amount” of confidence in scientists fell from 84 percent to 77 percent. And confidence in journalists fell five points, to 40 percent.

Writing about topics like climate change can feel like preaching to the choir, says Rachel Feltman, executive editor of Popular Science, reaching only an audience that already has faith in science and failing to break through to others.

“There’s always going to be a group of core science readers who have a big interest in nerdy new developments,” says Niall Firth, editorial director for digital at MIT Technology Review. “But for others, those stories can feel like you’re coming in halfway into a conversation. You don’t really know what’s been said before, and you don’t really know why you should care.” The tips cited in this chapter might help make them feel welcomed into a story. That’s what this chapter is for.

Attempts to make popular science more, well, popular, can backfire, though. The discovery of an exoplanet could be blown out of proportion, as in this 2021 story in The Irish Times: “Exoplanet discovery may ultimately answer the question ‘Are we alone?’” New developments in physics — even big ones — do not necessarily “break” physics, despite what Business Insider might lead you to believe. There’s a balance in making stories more appealing and accessible to readers, while not sensationalizing or overhyping what’s really happened.

In the rest of this chapter, I’ll explore some ways writers and editors can maximize the audience for popular-science stories without sensationalizing or inaccurately reporting what’s happened, or misleading readers. Science is a slow and methodical process — but it’s also a way to deepen understanding, spark wonder, and engage your readers.